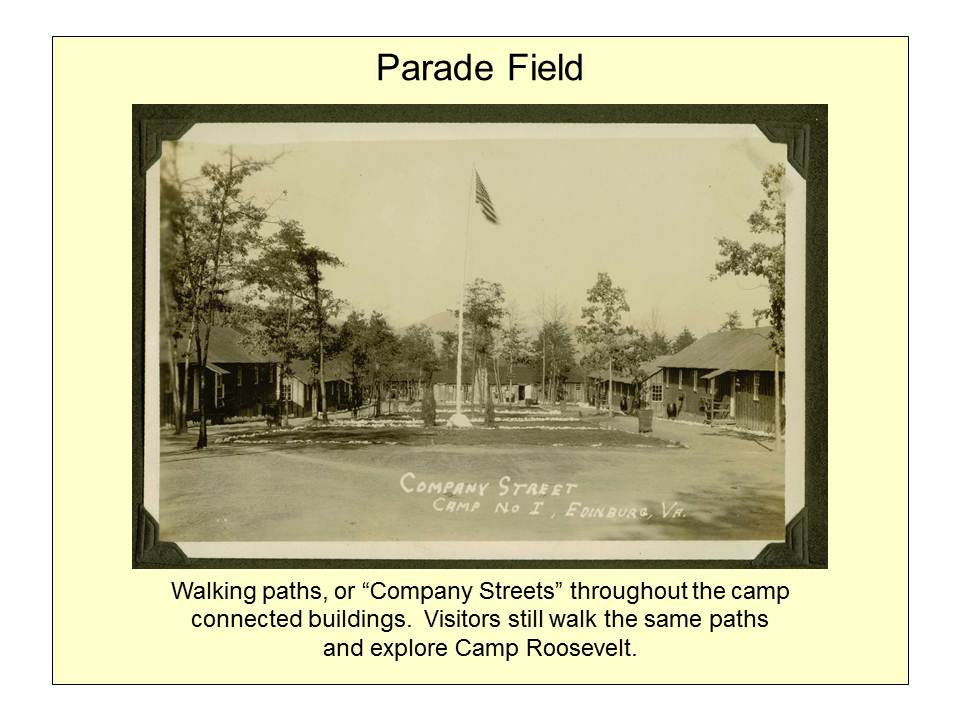

As visitors walk the existing paths of Camp Roosevelt, the stone foundations of buildings are visible throughout the area and elave a lasting mark on the story of camp life. This presentation show photographs of the original buildings and explains how they were used. Developed as an education tool for scout groups the slide show is available for distribution by contacting CCC Legacy.

Camp Roosevelt, NF-1

First CCC camp in the Nation

Background

Camp Roosevelt was the first of many camps to spring up across the country. The CCC was part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, and was designed to provide jobs for thousands of unemployed young men to work towards conservation on a national scale. 4

When President Roosevelt took office in 1933 he faced a nation that was bankrupt in money and spirit. One of his first acts was to ask Congress for a large appropriation for emergency conservation work. This resulted in the passage, in March 1933, of the Emergency Work Act, or as it came to be called the “Civilian Conservation Corps.” It was a program to recruit thousands of young men to work in forests, parks, lands and water in the preservation and use of basic natural resources. 2

The CCC was a result of Senate Bill 598 that the President introduced March 27, 1933. The bill cleared both houses of Congress in four days and was on the President’s desk for signature on March 31, 1933. The first camp opened on April 17, 1933; by July 1 there were 275,000 enrollees in 1,300 camps across the country. 2

Robert Fechner, a Boston labor leader, was appointed National Director by Executive Order 1601 on April 5, 1933. He established rules and regulations, allocated funds, approved the establishment of camps and was, in general, responsible for the overall operation of the camps. 2

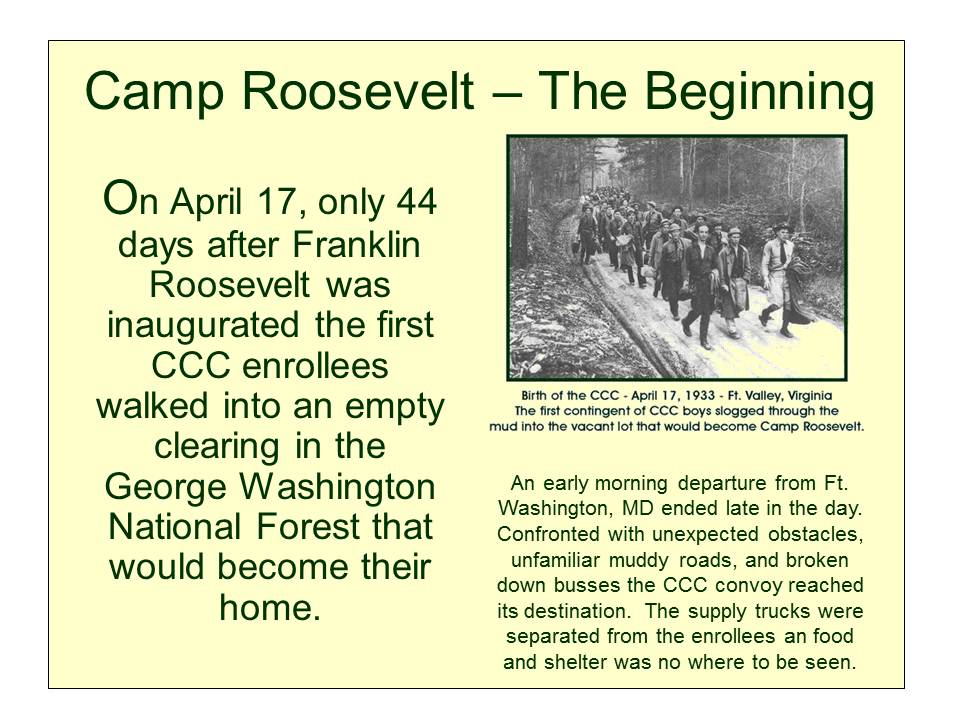

The U.S. Department of Labor chose a selection agent for each state to certify the selected enrollees to the War Department. On April 10, 1933, the first quota of 25,000 men was called, and on April 17, 1933 Camp Roosevelt was located on the George Washington National Forest. Every state in the nation had one or more camps. (Virginia had 63 camps.) The number of camps in a state depended on many factors, including the number of enrollees from that state and the number of projects the state had readily available. As there were not enough projects in the East to take care of eastern men, many were sent to western states. 2

The CCC was an immediate success, due in part to the cooperation among different federal agencies. The Department of Labor was responsible for the selection and enrollment of applicants. The Department of Agriculture and Interior planned the work for each state. The Army and Navy supervised the construction and operation of the camps and devised ways to transport enrollees to their designated areas. Finally, the USDA Forest Service and the National Park Service oversaw camp projects.4

The program had strong public support and enrollment was consistently high. By 1942, at the program’s end, nearly 3 million men had found employment in the nearly 4000 camps across the country and in Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. 4

Enrollment Eligibility

Men between the ages of 17 and 25 who were unmarried, out of school and unemployed were eligible for enrollment. They were paid $30.00 a month, $25 of which was sent home to their families or if they had no family, it was held in an account for the enrollee until they were discharged from the camp. The boost to the economy brought by these checks was felt throughout the country. There was a social impact. These young men were taken off the streets. They traveled far from home and performed useful work in a healthy environment. Over 110,000 illiterates learned to read and write. The men worked 40-hour, six-day weeks, in crews of 48. Each crew had a leader and assistant leader who were in charge in the barracks and on the job. These men received $45 and $36 a month, respectively. There were 16 Local Experienced Men (LEM) hired from the areas surrounding the camps to help inexperienced crews learn necessary skills. Above them in rank was the group foreman, who attended a CCC training school and then was assigned to a camp as part of its technical staff. Foremen were paid $140 a month to serve as on-the-job supervisors. Each camp also had a superintendent and Army officers responsible for day-to-day operations. 4

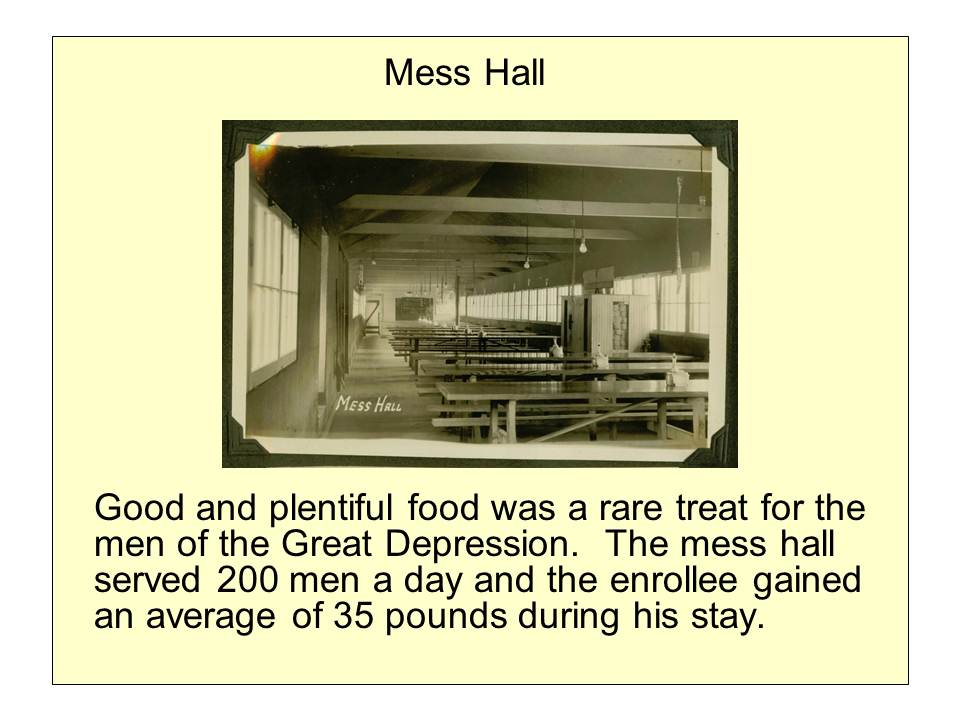

In addition to the monthly salary, men were given food, clothing, shelter and medical care. Their term of enrollment lasted from six months to two years. Enrollees gained an average of 12 pounds each from the government rations.4

The induction of the first enrollee on April 7, 1933 occurred only 37 days after Roosevelt’s inauguration. Camp Roosevelt began operation only 12 days after the President signed the CCC bill into law.4

The Early Days

Excerpts from a speech given by George Dant, Camp Roosevelt 1991. He was in the first contingency of men at Camp Roosevelt.

…It was late afternoon when approximately 200 men walked to the crest of the mountain just above Camp Roosevelt. Looking down the road, there was nothing but open sky and one single canvas covered army truck in a 10-acre clearing. The local mountain and townspeople were standing around the fringes of the newly cleared area. They had come from Crisman Hollow, Edinburg, Mt. Jackson, and Luray and as far away as New Market. These folks, waiting for something to happen, would be disappointed as the CCC boys straggling in had just pushed their Grey Hound Busses to the crest of the mountain and many had never before been in the mountains. The supply convoy had become separated and lost. The supply trucks had taken the valley road – looking for Luray, but couldn’t find it in the Edinburg/Mt. Jackson Area. The single truck in the clearing contained only folded canvas army cots. There was no food, water, blankets, tents or shelter except for what the Forest Service people brought with them, and there wasn’t enough to go around, so no one used it.

The young men had been up since 4:30 am had breakfast at 5 am. The chartered buses were late and did not depart Fort Washington MD until 9 AM. A brown bag lunch had been provided consisting of a bologna sandwich, a hard-boiled egg and a cookie. This was before the “C” ration. Soon after the men arrived, the mess officer Sergeant Moose and the cook Max Plotkin drove up in private automobiles. They quickly grasped the situation and retreated towards town in search of the missing trucks – especially those related to food and cooking facilities.

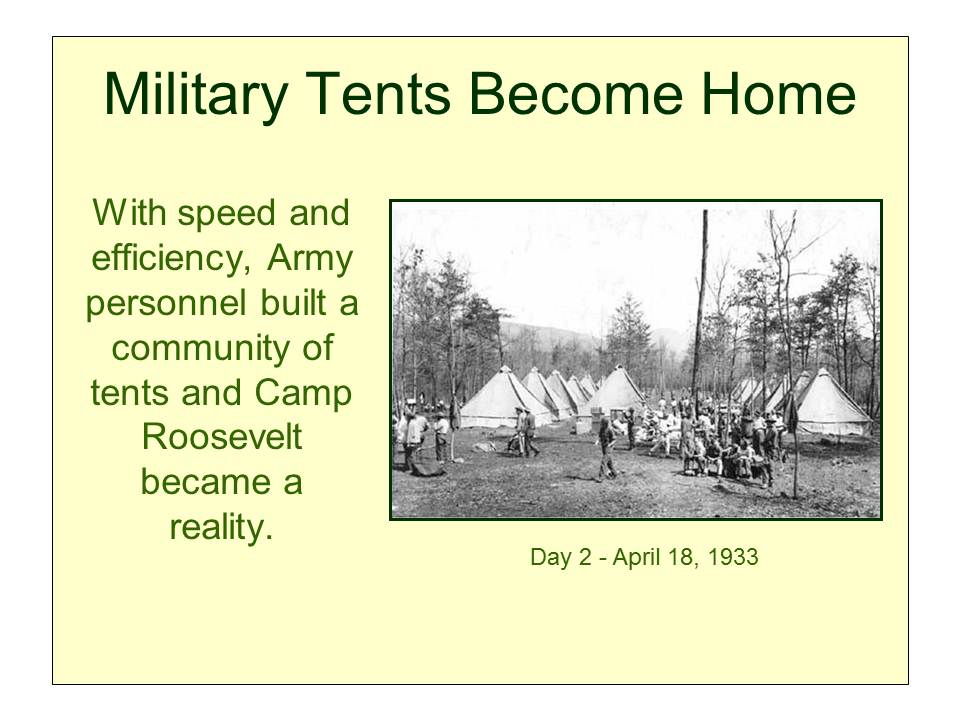

The men had nothing to do, but set up the cots and wait. The weather took a turn and soon rain and lightening filled the skies. The boys looked to their duffle bags for rain or overcoats as the area they sat in had been cleared of all foliage. In early evening a truck arrived with lanterns and low voltage battery lights. Sergeant Moose returned after virtually clearing out the towns of hot dogs, hamburger, salmon and bread. Around mid-night, a large van arrived with blankets and tents. The storm had subsided long enough to unload the blankets and tents.

During the next few days many of the boys who had wandered away the first day, returned in a variety of conveyances – some in private vehicles of still curious locals, some in supply trucks or military vehicles and in some instances the local sheriffs or constabulary returned the enrollees.

The entire cleared area was a lake of mud. Constant movement of personnel and continued rain created a black, soupy substance. Field stoves were covered with leaking tarps. Cooks were wet to the skin. Personnel were deserting. Water had to be hauled from Passage Creek as no well had been drilled. The water was from Lister bags containing chlorine. The latrines were uncovered, open, straddle-trenches. It was debatable whether the rain or personnel would fill them first.

The camp was a bleak place. With the arrival of Locally Experiences Men (LEMs) the depleted complement was brought back to full strength. LEMs were the newfound brothers, partners, friends and dads of all the enrollees, who taught, trained, guided and transformed city boys into men of the next generation. These same men, who later served in WWII, put down tyranny and brought back some semblance of peace to the world.

Many of the early enrollees at Camp Roosevelt received a liberal education. While the recreation building was under construction, word went out to Washington DC that any kind of books were welcome at the camp. Not long afterward, a huge truckload of books arrived. The boys eagerly grabbed them up and took to reading like you’ve never seen. It was almost impossible to separate a boy from his book. Any boy – any book. It was soon discovered that hundreds of donated books were discarded from DC libraries because they were uncensored – or what we know today as pornography. They were almost too educational. The recreation officer, Captain Wilkinson, quickly had them replaced with those of a more fitting nature.

Supply, Mess sergeants and cooks did a magnificent job! Increased food allowances were made to all CCC camps, depending on their location, sources of supply and longevity. The regular army was feeding its troops on $0.45/day and Camp Roosevelt was allowed $1.50/day. A typical breakfast consisted of oatmeal, milk, bacon, eggs, potatoes, bread, butter and coffee. Dinner was: frankfurters and sauerkraut, boiled potatoes, creamed carrots, peas, rice pudding, bread and butter and coffee or cocoa. Supper: Iris Stew, cole slaw, mashed potatoes, string beans, bread and butter, custard pudding, coffee or iced tea.

Never in history did a nation ever receive so much lasting value, for its investment, as that from the CCC. Many former enrollees of Roosevelt’s Tree Army – the CCC — say that those were the happiest days of their lives. I agree, and I don’t believe there will ever again be anything like it.” George Dant, 1991

Later Years at Camp Roosevelt, NF-1

One enrollee – Moon Mullins who arrived at Camp Roosevelt in 1934 recalls his early experiences. He remembers his arrival at the Edinburg train depot from there he and other enrollees were driven to camp. “We came over the mountain in a covered truck. We couldn’t see; we didn’t know where we was goin.” Arriving at night, his first glimpse of the camp wasn’t too encouraging. “It was a lonesome sight to be called home, but the longer I stayed the better I liked it.” 4

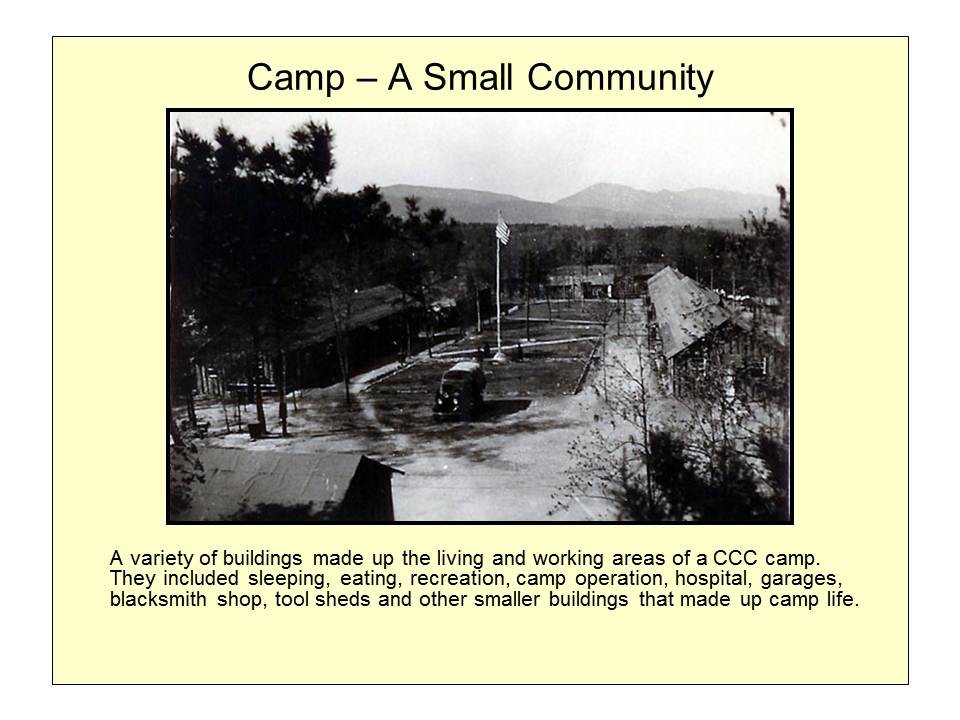

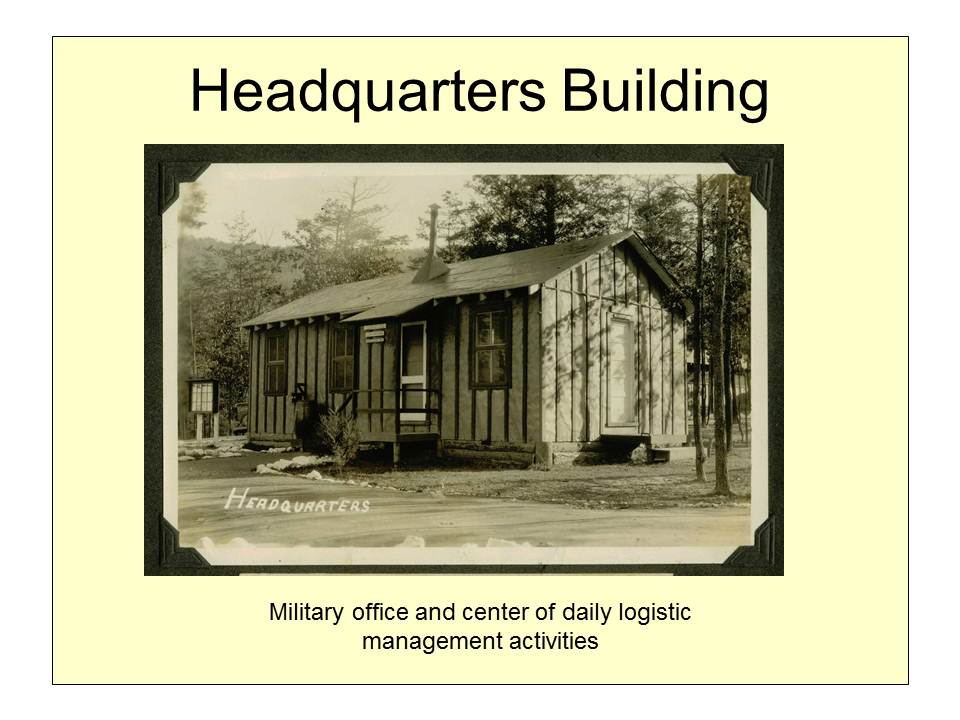

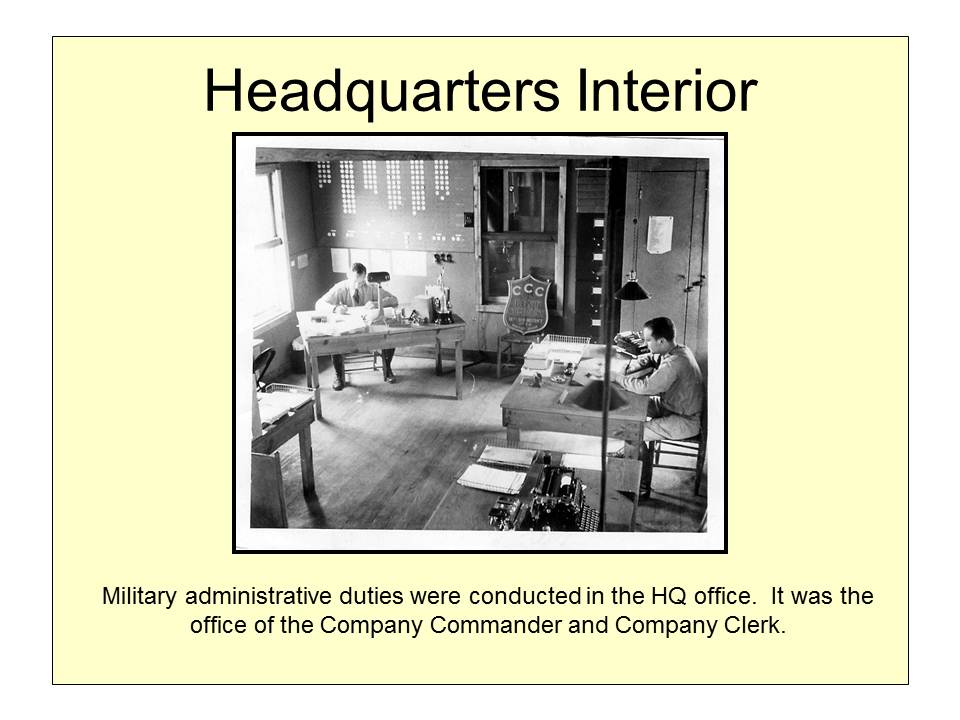

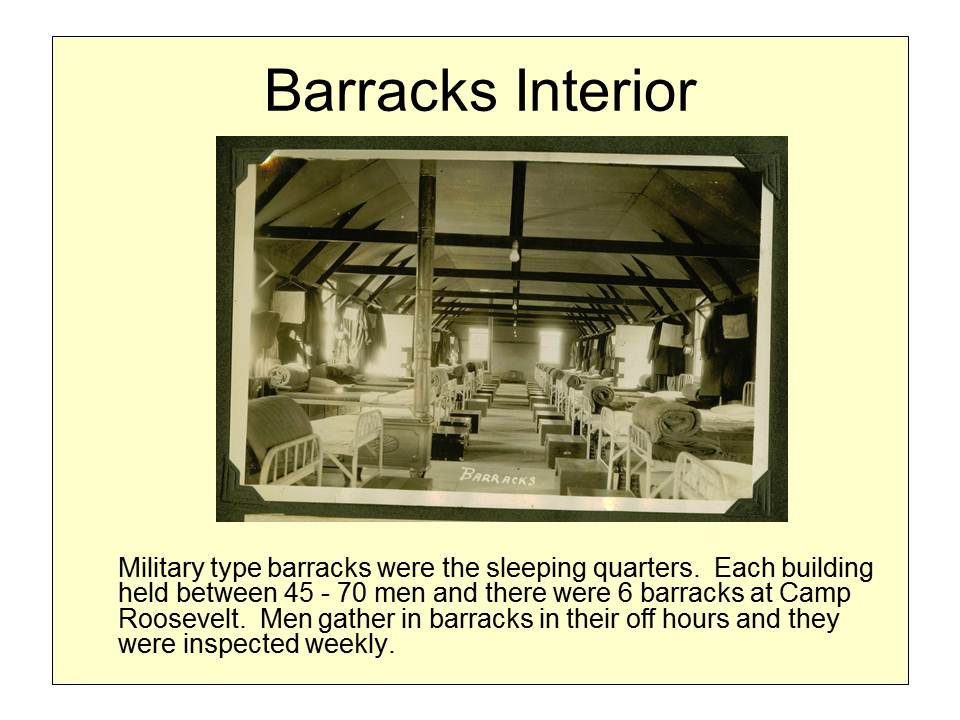

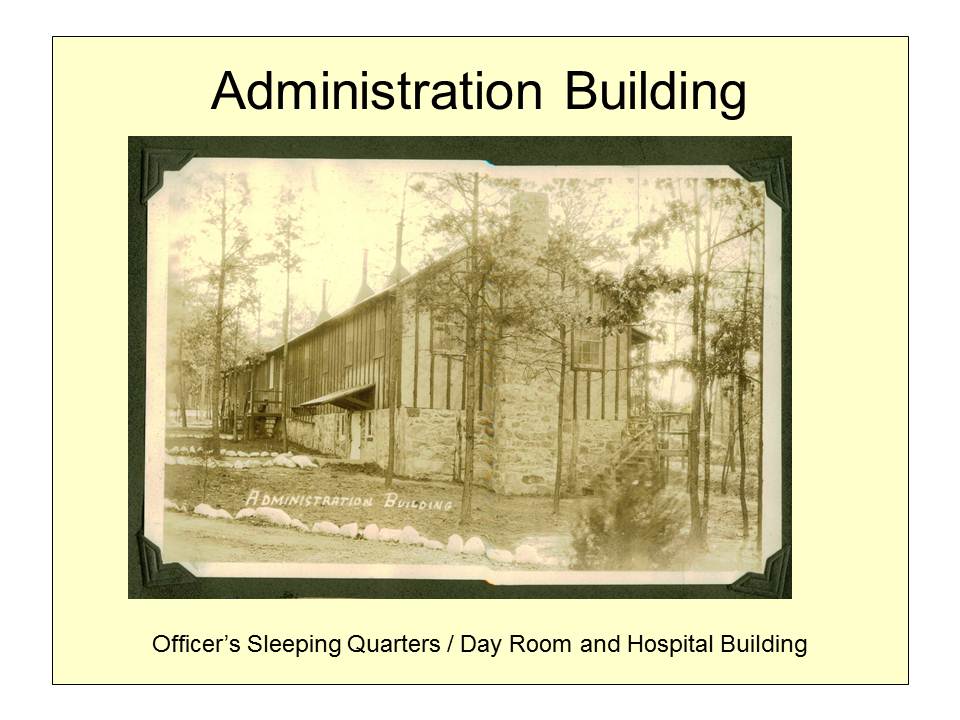

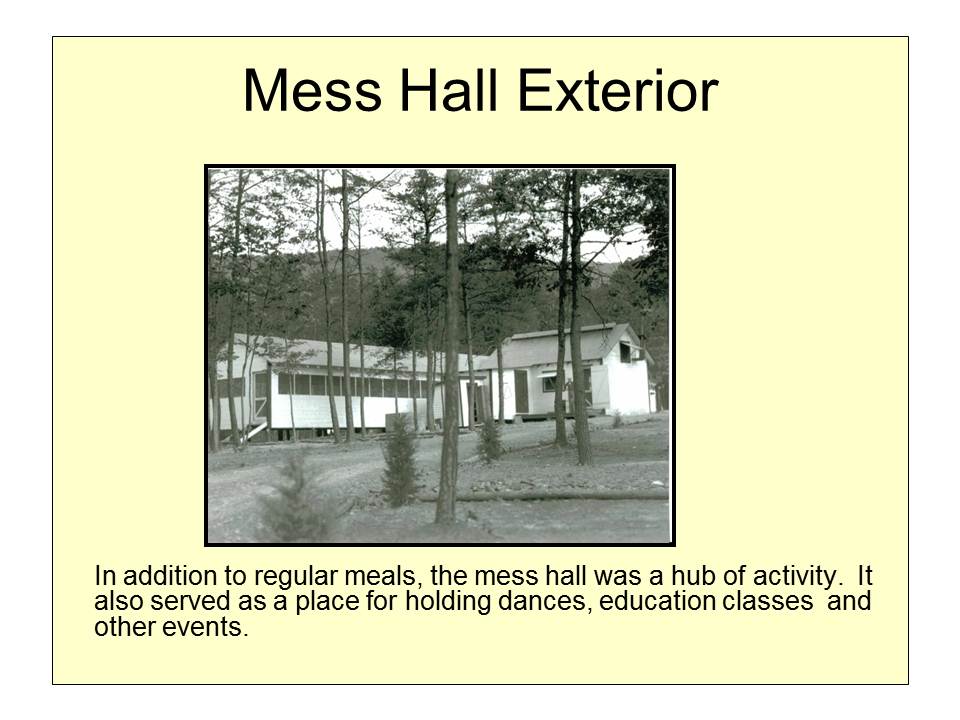

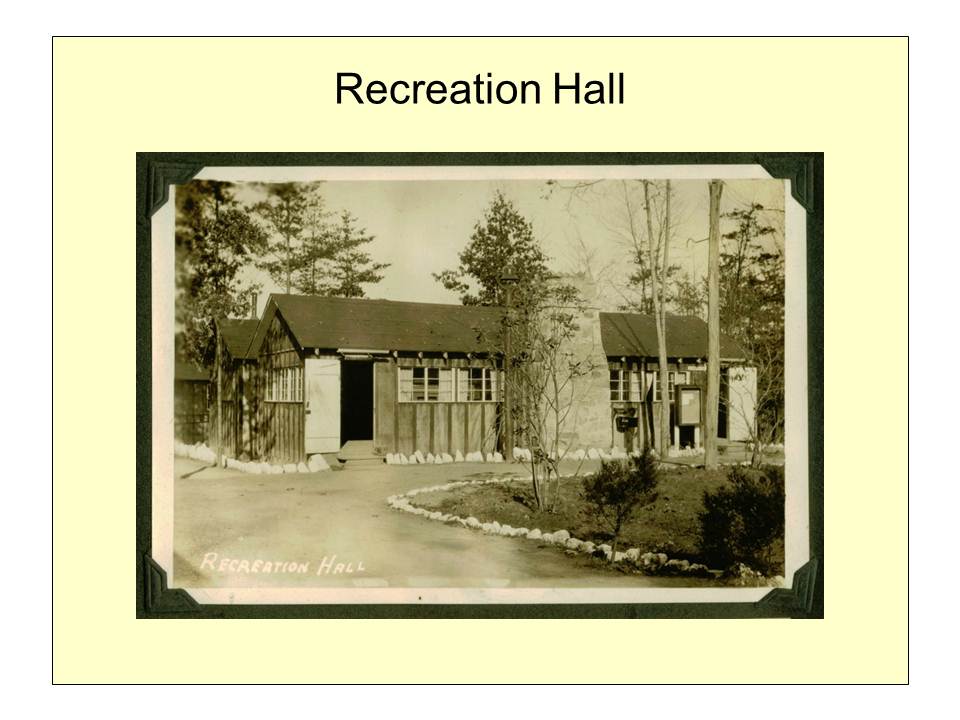

When Camp Roosevelt first opened, the men slept in tents. By 1934, four barracks had been built. Each barracks held 48 men, who slept “head to foot” on iron cots and cotton mattresses, with two large coal stoves in each barracks for heat. The camp continued to expand, and by 1942 there were 24 buildings, including six barracks, a recreation hall, education building, wash house, officer’s quarters, infirmary, mess hall and kitchen, Army office and garage and truck shed.4

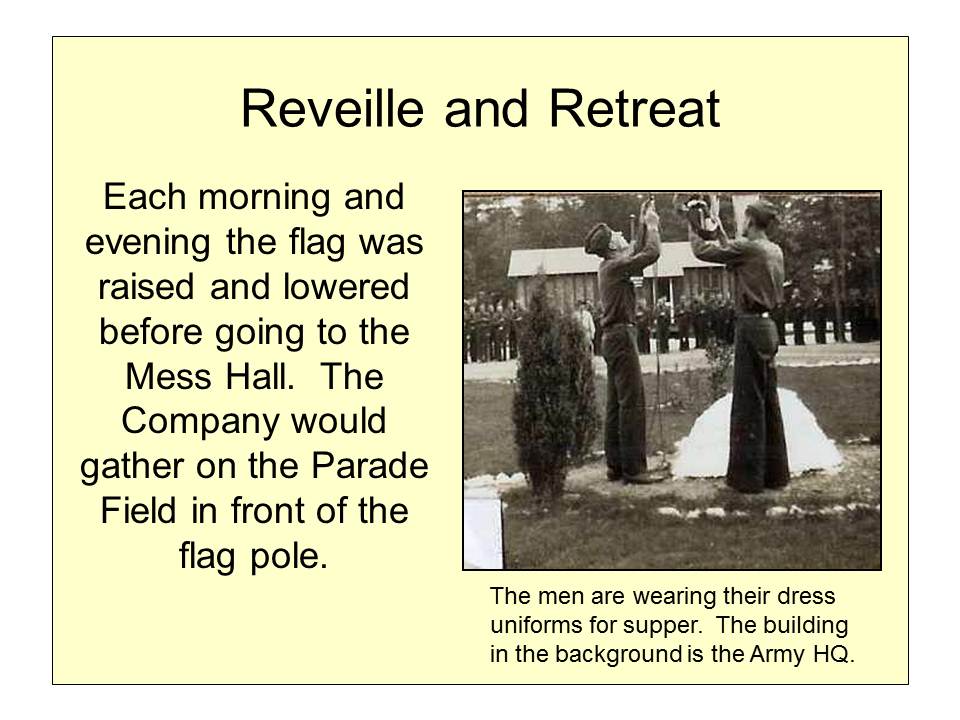

Workdays followed a typical pattern. The men rose at 6 AM made their bunks, straightened the barracks and went to the mess hall for breakfast. Of the food, Mullins recalls, “I can’t say it was like home-cooked, but we always had plenty.” The best meals were served on holidays, when the menu included treats such as turkey, ham, stuffing, mashed potatoes and apple pie.4

After breakfast, the men donned Army issue work clothes — heavy khaki colored shirts, pants and jackets – and went across the road from the camp to Forest Service headquarters, where they were assigned their details for the day. A foreman leader and assistant leader supervised each. The crews completed a variety of jobs. They built telephone lines, roads and bridges; planted trees, fought forest fires, stocked streams with fish, stocked the mountain with deer and worked on roadside improvement. They also constructed Elizabeth Furnace Recreation Area, New Market Gap and Little Fort Recreation Areas. They built or improved Crisman Hollow Road and SR 678 that runs through Fort Valley.4

Their workday lasted until 4:30 PM with a 45-minute break for lunch. After dinner, back at camp the men were on their own. Some returned to the barracks to read or write letters or listen to the radio. Others went to the recreation hall to shoot pool, play poker or sit and talk. Also, at night or weekends, the men played basketball, volleyball, and football or went swimming. Liquor was not allowed in the camp, but according to Mullins, bootleggers would sneak around. One year a mother bear got killed so the men brought her two bear cubs back to camp. They stayed around getting into everything and sleeping in the men’s cots. Eventually they had to be returned to the mountain.4

One night a week, the men dressed in civilian clothes and drove trucks down the mountain to Edinburg. There they would go to the movies, bar or perhaps visit a girlfriend. The trucks returned to camp at 11:00 PM. If you missed the ride you had to walk the nine miles back to camp.4

Most things at camp ran smoothly. There were occasional fights, but not often. For punishment you might be banned from a trip to town or receive a reduction in pay.4

The camp infirmary took care of minor illnesses, more serious cases were sent to Walter Reed Hospital in Washington DC. Moon Mullins remembers only two deaths at camp during his 6 years as a CCCer and later as an LEM – one man was killed by falling rocks while working on roadside improvement, and the other died of an illness. Most men remained healthy and in good shape.4

Aside from the visible achievements, the camps taught discipline, good work habits and a trade to many who had little skills or working experience. These proved valuable once the men left the CCC, especially if they entered the military.4

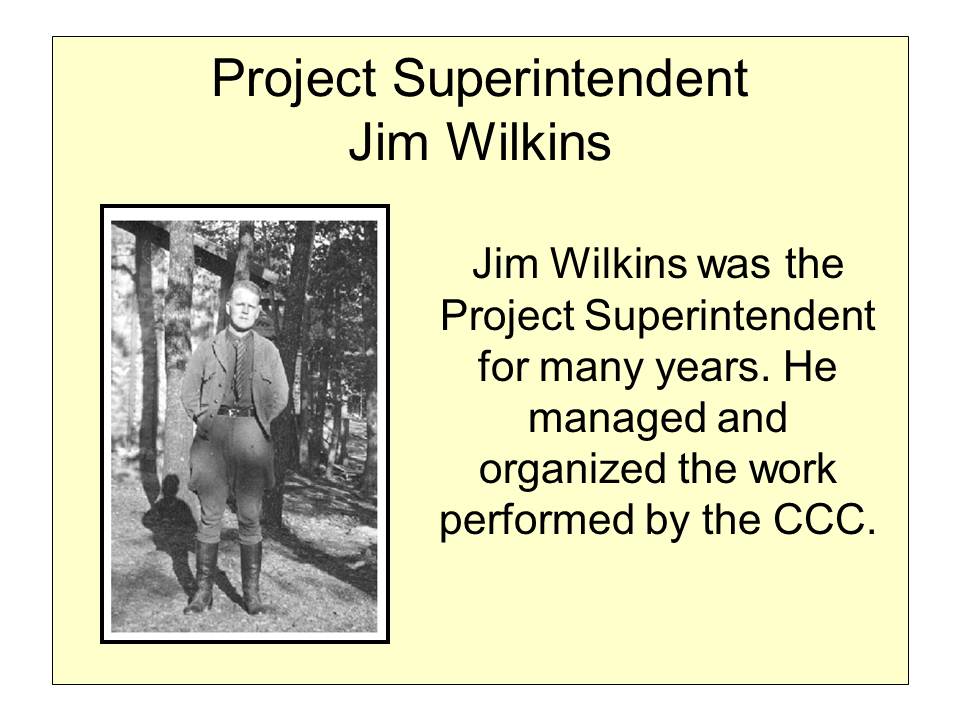

James R. Wilkins started work for the Forest Service in 1934. He became something of a troubleshooter and helped get camps started all over Virginia. He went on to become Superintendent of Camp Roosevelt in 1935 and stayed there until 1940.4

By 1940, due to the growing threat of war and the improvement in the nation’s economy there were fewer than 200,000 men in about 900 camps. The need for the program was rapidly diminishing. Although Congress faced great pressure in 1942 to abolish the CCC, the Corps was never abolished. Congress simply failed to provide funds for its continuance, so after June 30, 1942 it officially went out of existence. 2

Camp Roosevelt closed in 1942 and remained essentially abandoned until 1964 when Moon and Pearl Mullins wrote a letter to John Marsh, Secretary of the Army in hopes of making the area a recreation area. Three days later March replied saying he would pursue the idea. In 1965 a special committee awarded $55,000 to the project that was completed in 1966. The recreation area has 15 picnic sites, 10 camping units and two public restrooms.4

Camp Roosevelt NF-1’s local reunions began in 1977. Both Moon Mullins and James Wilkins were instrumental in getting these started but also keeping them going for over 24 years.4

The years of the CCC can best be summed up by James R. Wilkins Sr. “We worked long hours, and we put our heart and soul into it, and we loved it. With memories like those, how could they forget?”4

The Conclusion

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) made a significant contribution to the national forests of the nation. During the nine years of the CCC program, 1933-42, the CCC was instrumental in providing countless hours to reforestation efforts, fire observation and fighting, and opening large areas of virgin forests through needed trail and road construction. Although the program was designed 50 years ago to help the unemployed of our country, their contributions to sustained yield forestry, in its most general sense, are now being appreciated.5

Fechner Memorial Forest

On, February 4, 1941, President Franklin D, Roosevelt signed an Executive Order designating the Robert Fechner Memorial Forest as the Massanutten Unit of the George Washton National Forest as described in proclamation, No. 2311 of November 23, 1938. This memorial forest was created in honor of Robert Fechner, the first director of the Civilian Conservation Corps.

The National forest lands within the boundaries of this memorial forest, and those subsequently acquired within its boundaries shall continue to have a national forest status, but their administration development and management by the Forest Service shall reflect the spirit and intent of the memorial designation. This site was chosen for being the site of the first CCC camp in the country and for its suitability of a “model multiple-use forest area.” (From the Forest Service and the CCC, 1982) As far we know, as of 1965, the executive order still stands although the memorial forest is not longer listed on current maps.

Bibliography

- Davey (Richman) Tisha, “Camp Roosevelt NF-1, Term Paper, 1969

- Harr, Milton, The CCC Camps in West Virginia, 1992

- http://fs.jorge.com/archives/default.html (FS History Website)

- Leonard, Carrie, “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” Curio, Summer 1984

- “Roosevelt’s Tree Army”, A Brief History of the Civilian Conservation Coirps, National Association of CCC Alumni

- Speech given by George Dant at Camp Roosevelt Reunion, 9/1991